The prototype of Japanese ramen is introduced

Noodles introduced from China in 1488

In 1488, there is a record of the first time noodles called “Keitai-men” were eaten in Japan. Surprisingly, alkaline water was used here, which gave the wheat flour noodles their firmness and unique elasticity. It is surprising to learn that this is almost the same formula used for ramen noodles today. Although the term “ramen” did not exist at the time, it is believed that the prototype for Chinese noodles in Japan was born during this period.

Soba for Entertainment” in 1697: An Anecdote about Mitsukuni Mito and Shushun Sui

In Japan, Mitsukuni Mito, the lord of the Mito domain known as “Mito Komon,” is said to have first tasted Chinese noodles in 1697. It is said that when the Confucian scholar Shushun Sui entertained Mitsukuni, he served him his own soup noodles. This is said to be the first time that Japanese people officially ate Chinese noodles, but at the time, opportunities for ordinary people to eat Chinese noodles were very limited, and the dish did not spread widely throughout the world. However, there is no doubt that it was through this cultural exchange that the groundwork was gradually laid for the ramen to take shape in later times.

The Dawn of Ramen

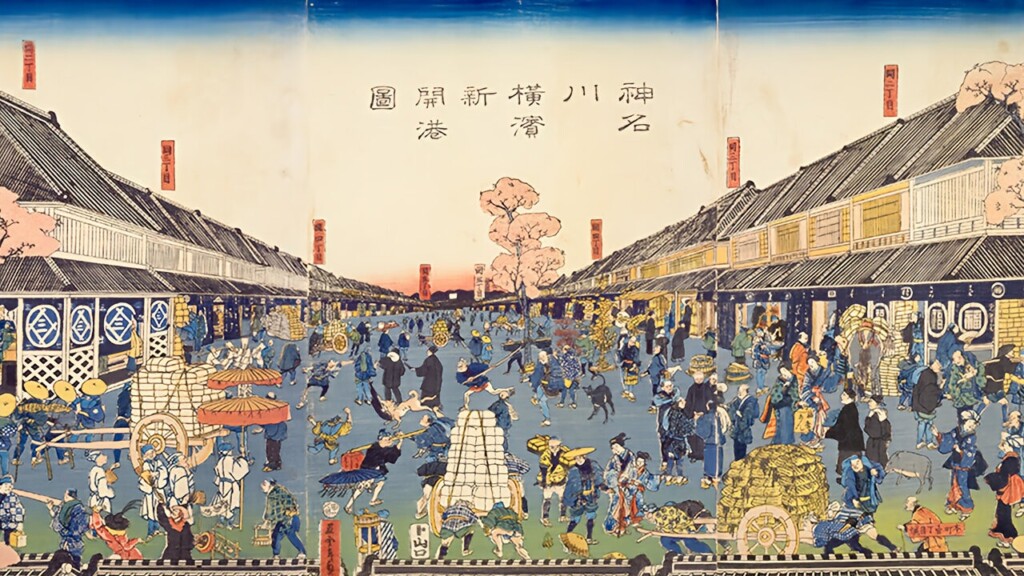

Major shift after 1859, influx of different cultures due to opening of ports

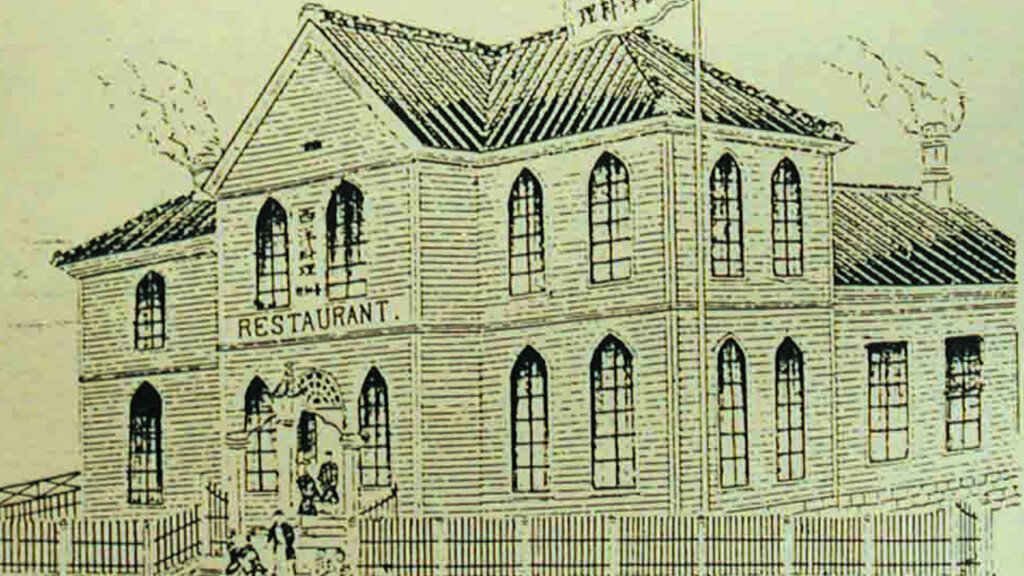

The opening of ports in 1859 triggered the flow of various foreign cultures into Japan at once. People from abroad flocked to port cities such as Yokohama, Kobe, and Nagasaki, including restaurants serving Chinese noodle dishes. Against this backdrop, Japan’s first Chinese restaurant opened in the Yokohama settlement area in 1870, and foreign gourmet food began to come to people’s attention in earnest.

The Spread of Chinese Noodles in Japan: Hakodate’s “Yowaken” and “Nankin Soba

The 1884 Hakodate newspaper advertisement for “Nankin Soba” by “Yowaken” in Hakodate is also not to be overlooked. This may be the first official advertisement of “Chinese noodles” in Japan, and is a valuable historical document. However, it is not certain whether this “Nankin Soba” was “soup soba” like ramen noodles today. However, as the name “Nankin Soba” suggests, it is certain that noodle dishes of foreign origin were gradually taking root in Japan.

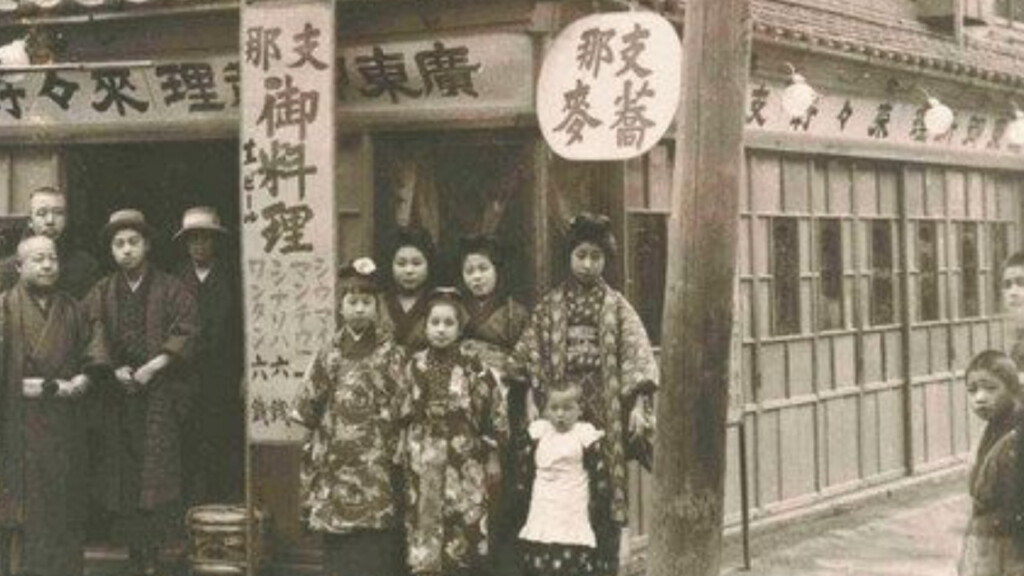

Spread of Chinese restaurants and abolition of reservations

After the reservations were abolished in 1899, Chinese restaurants gradually spread to other parts of Japan. In the same year, Chen Heijun invented Nagasaki chanpon at Shikairou in Nagasaki. Around 1906, the number of Chinese restaurants catering to the masses began to increase in the Kanda and Hongo areas of Tokyo, laying the foundation for Chinese noodles to become deeply integrated into people’s daily lives. It was during this early period that the dish that would later become known as “ramen” flourished.

Ramen at “Asakusa Rairaiken” in Tokyo, Japan and the Beginning of a Big Boom

In 1910, Kanichi Ozaki opened “Asakusa Kuraiken”, which sparked the ramen boom that spread throughout Japan. Noodle dishes, which at the time were still called “shina soba” or “nankin soba,” became more familiar to the general public and finally showed signs of spreading in earnest around 1912, when a Chinese cookbook for home use became a bestseller.

An Unexpected Turning Point Brought about by the Earthquake: Spreading Ramen throughout Japan

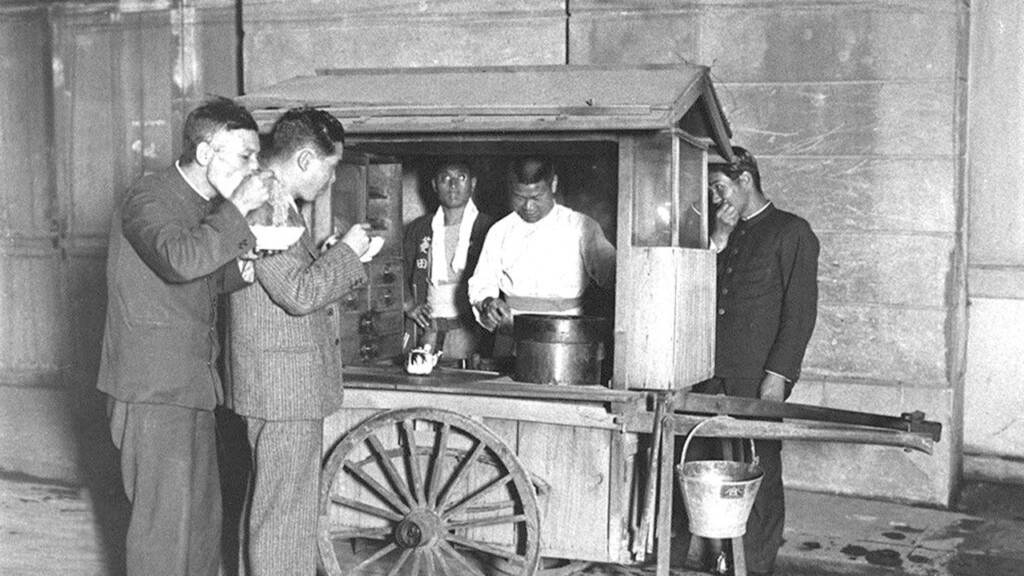

The Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923 caused a great deal of tragedy, but this event also provided an opportunity for “ramen stalls” to spread from Tokyo and Yokohama to the rest of the country. The owners of these stalls moved to new locations after the disaster and began their businesses, spreading ramen throughout Japan. The first “Genraiken” ramen store opened in Kitakata City, Fukushima Prefecture, around 1925, and this movement gradually spread to other regions of Japan.

Various long-established ramen stores with roots in the first half of the Showa period

In the 1930s, noodle restaurants opened one after another in Osaka’s Umeda district and Kyushu, Japan, and in Kyushu, “Nankin Senryo” opened in 1937. The roots of the tonkotsu (pork bone) culture that would later become famous in places like Hakata and Kumamoto were already beginning to show themselves. Meanwhile, many long-established restaurants, such as Kyoto’s Shinpuku Saikan and Hida Takayama’s Masago, were founded around this time, and a succession of long-selling restaurants that continue to this day can be said to be a characteristic of this early period.

Ramen Takes Root in Japan

Postwar Confusion and Ramen as Optimal Cuisine

After World War II began in 1939, many ramen stores in Japan were forced to temporarily close. However, after the war ended in 1945, people returning from the war began opening ramen stalls throughout Japan. Ramen, made with inexpensive flour, was highly nutritious and a “perfect dish” for the harsh postwar food situation. Black markets and other such places popped up all over the country, and the ramen served there relieved the hunger and fatigue of the Japanese populace.

Reforms in Kyushu and Sapporo, respectively

In 1947, “Sankyu” in Kurume began serving a cloudy pork bone soup in earnest. This is said to be the origin of today’s Kyushu ramen, and Sankyu made a revolutionary impact by introducing a thick, cloudy tonkotsu (pork bone) soup, while Nankin Senryo, which had been established earlier, had a light tonkotsu soup.

Meanwhile, in Sapporo, “Ramen Yokocho” was established in 1951, and in 1954, Mr. Morito Omiya of “Aji no Sanpei” developed miso ramen. The rich miso soup matched the local cold climate, and was the decisive factor in creating the “Sapporo miso ramen boom” that followed.

Originating in Japan, the budding new trend of “Tsukemen” (dipping noodles)

It should not be overlooked that Kazuo Yamagishi developed “Tsukemen” at “Taisho-ken” in Nakano, Tokyo, Japan, in 1955. Who would have thought at the time that this style of noodle, initially called “morisoba,” would draw huge lines of customers and eventually spread to the rest of Japan? While the individuality of soups such as tonkotsu (pork bone) and miso (soybean paste) swept the nation, an unusual way of eating ramen called tsukemen emerged, further expanding the range of ramen.

Ramen noodle development period

The Impact of 1958: The Instant Ramen Revolution

In 1958, Nissin Foods’ “Chicken Ramen” was launched. This was the decisive factor in the spread of the term “ramen” nationwide, beyond the names “shina soba” and “chuka soba. In the same year, “Chinchin-tei” in Musashisakai, Tokyo, invented “abura soba” (oil soba), and new styles of ramen were born one after another in the ramen world. The following year, Marutai released “Chicken Flavor Stick Ramen” in Fukuoka, and the instant food market itself began to expand rapidly.

Innovation continues throughout Japan

In the 1960s, Japan saw an increase in the number of unique regional menus, such as “Karamiso Ramen” invented by Ronshangai in Akayu, Yamagata, and “Taisho-ken” by Kazuo Yamagishi in Higashi-Ikebukuro, Tokyo, beginning full-scale operations. Ace Cook’s Wantanmen (1963) and Sapporo Ichiban series (1966) were also across-the-board hits, and ramen became an indispensable part of the Japanese household table and a late-night snack. A succession of classic products were introduced, including Myojo Charmera and Nissin’s Demae Iccho.

Miso Ramen Penetration Nationwide and the Beginning of the Ie-kei Ramen Lineage

Sapporo miso ramen exploded in popularity when it was demonstrated and sold at Hokkaido product fairs and department store events. 1964, when Sapporo’s “Kumasan” demonstrated at the Takashimaya Department Stores in Tokyo and Osaka, its rich miso soup created a huge sensation and quickly gained fans. 1974, Yokohama’s “Yoshimuraya opened in Yokohama in 1974, giving birth to a new genre of ramen called “Ie-kei Ramen. The combination of tonkotsu (pork bone) and soy sauce with thick, straight noodles gained a growing following, especially in the Tokyo metropolitan area, including Tokyo and Kanagawa Prefecture in Japan.

The Global Impact of “Cup Noodle

In 1971, Nissin Foods introduced Cup Noodle, which further accelerated the ramen revolution. Compared to conventional bagged noodles, cup noodles dramatically improved convenience and portability, and became an explosive hit in Japan and abroad. 1973 saw the opening of the Tsukemen Daioh Tsukemen specialty restaurant, and from around 1975 there was a boom in back fat ramen. The instant ramen market and brick-and-mortar ramen stores both continued to develop.

Local ramen and town revitalization throughout Japan

In the 1980s, various regions in Japan began using their unique ramen styles as a means of revitalizing their communities. In 1984, Kitakata City in Fukushima Prefecture gained nationwide attention as the “Ramen Town.” By 1985, influenced by movies and gourmet television programs, ramen came to be appreciated as a gourmet yet accessible dish for the masses. Establishments such as “Ippudo” in Hakata, which opened in 1985, and “Shinasobaya,” founded in 1986 by Sano Minoru, known as the “Demon of Ingredients,” prominently showcased their dedication to quality and were frequently featured in the media. This period eventually came to be known in Japan as the “Ramen Warring States Period.”

Major Events of 1994

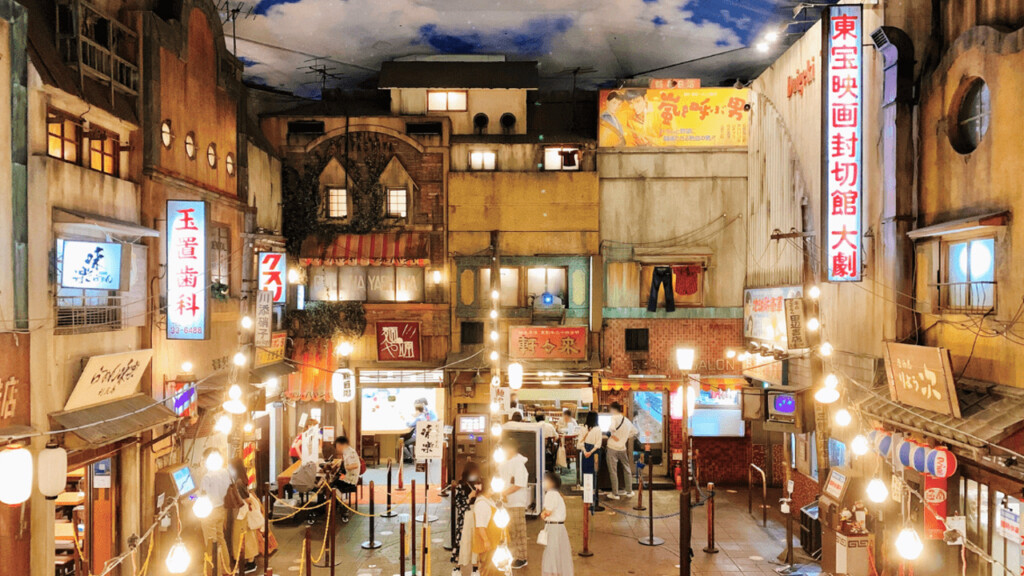

In 1994, the “Shin-Yokohama Ramen Museum” opened its doors. This theme park-style facility, which brought together famous ramen shops from all over Japan, marked the beginning of ramen being enjoyed not just as a meal but also as a form of entertainment. As a result, people became increasingly eager to explore regional differences and the unique dedication of individual shop owners.

The Era of Ramen Diversification in Japan

Around 1996, unique ramen stores opened one after another

Around 1996, the Japanese ramen industry saw the emergence of unique establishments that would go on to lead the industry, such as “Menya Musashi” in Aoyama, Tokyo; “Kamon” and “Aoba” in Nakano, Tokyo; and “Kujiraken” in Yokohama, Kanagawa Prefecture. Proprietors across Japan pursued their passion, creating distinctive broths, noodles, and toppings, which further accelerated the diversification of ramen. At the same time, local flavors rooted in regions like Asahikawa, Wakayama, and Tokushima were prominently featured in the media, sparking an increase in opportunities for the “local ramen” boom to flourish.

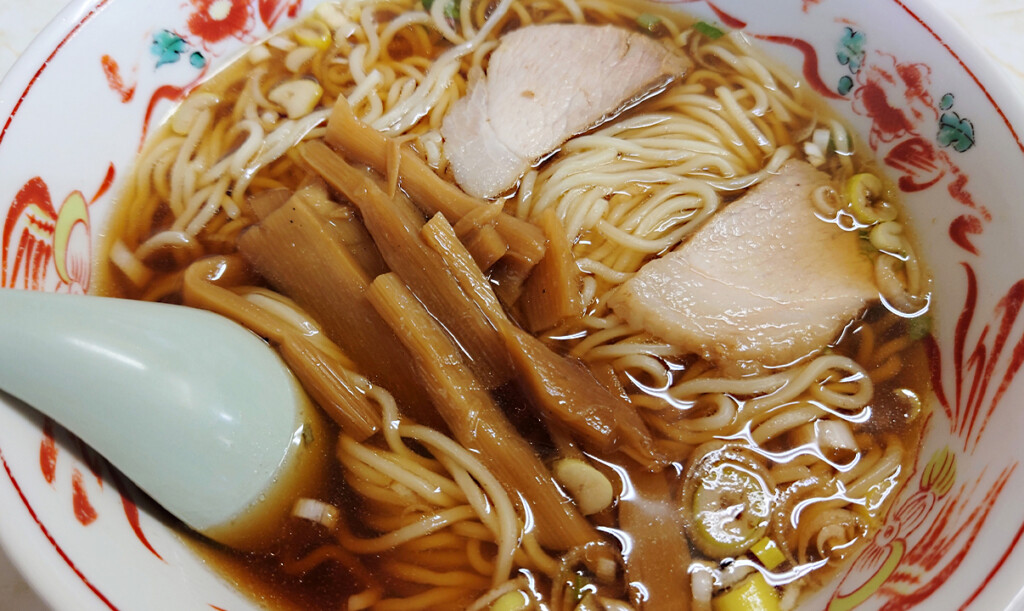

The “Local Ramen Boom” Focuses on the “Chefs”

Around the year 2000, a “Personal Ramen Boom” emerged in Japan, shifting the focus from “regions” to “individual chefs.” Not only the novelty of ramen menus but also the character and philosophy of the shop owners came into the spotlight. This period saw the rise of unique features such as thick seafood-based broths, double soups combining seafood and pork bone flavors, and ultra-thick noodles, each showcasing the distinctiveness of individual shops. Iconic establishments like “Ganja” in Kawagoe became representative of this movement, creating a new wave with their rich seafood dipping noodles, which gained a strong following among ramen enthusiasts.

Collaboration with Cup Noodles

Around 2001, cup noodles branded with the names of popular Japanese ramen shops began to emerge, ushering in a new era where the flavors of renowned ramen establishments could easily be enjoyed at home. At the same time, a new style known as “ramen dining,” characterized by elaborate interior designs, started gaining attention. This movement rooted a culture of enjoying ramen not just for its taste but also for the atmosphere and concept surrounding it. Additionally, legendary establishments like Taishoken and Jiro saw an increase in branch-off shops, with affiliated locations popping up nationwide around 2002.

The Evolution of Japanese Ramen: From Chicken Paitan and Brothless Styles to Light and Refined Varieties

In 2005, a new wave of chicken paitan ramen, featuring a rich flavor profile with the sweetness and aroma of chicken, became a trend. This innovative style of chicken-based soup challenged the dominance of traditional tonkotsu and seafood-centric thick broths. Around 2007, brothless ramen and mixed noodles (such as those dressed with fish roe) gained attention. By 2008, rich seafood dipping noodles became a major sensation, followed in 2009 by the rise of “doro-kei” ramen (ramen with a thick and sloppy broth). Around 2010, the spotlight shifted to “tanrei-kei” ramen, characterized by its clear and light soup. This surge of innovation led to the observation that “every year, something new trends in the Japanese ramen industry,” underscoring its dynamic and ever-evolving nature.

To the world and to new values

In modern times, many ramen restaurants such as Ippudo, Ichiran, and Kairikiya have opened overseas, introducing Japanese ramen culture to the world.

In 2013, Japanese ramen culture was introduced by “reimporting” stores from overseas, and the growing inbound demand has quickly led to innovations tailored to new user groups, such as vegetarian ramen and Muslim-friendly ramen. 2015 saw the opening of “Japanese Soba Noodles Tsuta” became the first restaurant in the world to win a star in the Michelin Guide, paving the way for ramen to be recognized as a gourmet cuisine as well.

As Japanese food is registered as a UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage and the number of foreign visitors to Japan continues to increase, ramen in Japan continues to undergo transformation.

Japanese Culture and Passion Engraved in Ramen

In ancient Japan, noodle dishes originating from China were a delicacy enjoyed only by the upper class. However, in the modern era, cultural exchange through the opening of ports brought these dishes into the public sphere. After World War II, ramen stalls opened across the country, transforming the dish into a “national food” that satisfied the appetites of the masses.

During this evolution, a variety of innovations emerged, such as “miso ramen,” “tonkotsu ramen,” and “tsukemen.” These variations eventually led to the development of instant and cup noodles, establishing ramen as a staple in Japanese households. Since the 1980s, media such as television, movies, and guidebooks have spotlighted renowned ramen shops across Japan, giving rise to the “local ramen” culture.

Entering a phase of “diversification,” ramen began incorporating new ingredients and techniques, elevating it to an “entertainment” experience that transcends borders. Ramen bowls crafted with the meticulous care and artistry of shop owners have even earned stars in the Michelin Guide, solidifying ramen as a symbol of Japanese culinary culture.

The history of ramen in Japan reflects the ingenuity and adaptability of the Japanese people, who embraced foreign influences and transformed ramen into their own. The future of Japanese ramen is undoubtedly one of further globalization and fusion, with new styles continuously emerging. Each bowl that captivates both visitors to Japan and locals alike embodies the richness of Japanese life and culture, along with an unrelenting spirit of exploration and creativity.